| Werner Hartenstein and the Laconia Incident |

|

22.00 hours,

September 12 1942. German submarine U-156 is on patrol in the South

Atlantic off the bulge of West Africa midway between Liberia and Ascension

Island. Peering through his periscope, Lieutenant Commander Werner Hartenstein,

U-boat ace and holder of Germany's highest military honour, the Knights Cross,

spots a large allied target sailing alone. He attacks and soon his

torpedoes have sent the 20,000-ton ship to the bottom of the ocean. But

Hartenstein's satisfaction at the kill soon turns to horror. Surfacing in

the hope of capturing the ship's senior officers and gleaning intelligence

information, Hartenstein is appalled to see over two thousand people struggling

in the water. For the target U-156 had just sunk was the former Cunard

White Star liner, the Laconia. Unbeknownst to Hartenstein, the Laconia was

carrying not only her regular crew of 136 but also 80 British women and

children, 268 British soldiers, 160 Free Polish troops and 1800 Italian

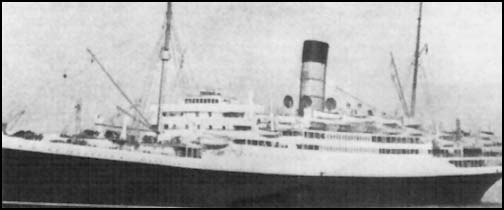

prisoners of war. Cunard postcards of the Laconia

There was not to

be a fairytale ending to Hartenstein's mission of mercy, however. The

following morning the four submarines, now with Red Cross flags draped across

their gun decks, were spotted by an American B-24 Liberator bomber flying out of

Ascension Island. Hartenstein signalled to the pilot requesting

assistance. Lieutenant James D. Harden USAAF turned away and notified his

base of the situation. The senior officer on duty that day, Captain Robert

C. Richardson III, had two choices: let the U-boats go, thus enabling them to

sink more allied shipping later, or order the B-24 to attack, almost certainly

condemning many of the Laconia survivors to their deaths. "Sink sub!" was the order Harden received. He flew back to the scene of the rescue effort and attacked with bombs and depth charges. One landed among the lifeboats in tow behind U-156 whilst the others straddled the submarine itself. Under attack, Hartenstein felt he had no option but to cast adrift those lifeboats still afloat and order the survivors on his deck into the water. The submarines dived and escaped. Many hundreds more of the Laconia survivors perished, but the Vichy French vessels managed to re-rescue about 1100 later that day. South African seaman, Tony Large, endured 39 days adrift in an open life boat before he was finally picked up.

The Laconia

incident, as it became known, was to have far-reaching consequences. Until

then it was common for German submarines to assist torpedoed survivors with

food, water and directions to the nearest land. But as his U-boats had

been attacked whilst mounting a rescue mission under the Red Cross flag, Admiral

Dönitz gave the order that henceforth all rescue operations were prohibited and

survivors were to be left in the sea. His Laconia order was used to help

convict Dönitz of war crimes at Nuremberg in 1946 even though American

submarines in the Pacific operated under the same instructions. He was

sentenced to 11 1/2 years, spending most of that time as a companion of Rudolf

Hess in Berlin's Spandau prison. But at least Dönitz survived the war and

lived into old age. He died on Christmas Eve 1980 at the age of 89, his

funeral being attended by thousands of old comrades including over 100 holders

of Germany's highest military honour, the Knights Cross, plus many senior

officers of the post-war, west-German Federal Navy. Werner Hartenstein and his crew were not so fortunate. Six months after the Laconia incident, on 8th March 1943 whilst on patrol east of Barbados, U-156 was depth-charged by another American bomber. She was sunk with all hands. © 2000 - 2002. All rights reserved. Text only. Photos and map courtesy of http://uboat.net Werner Hartenstein's Naval Career

|